Gazer, at its core, is a film about voyeurism and humanity’s innate compulsion to not just want to be voyeurs, but to understand and make sense of the people who are being spied on. People, by nature, have an urge to act as a storyteller and connect disparate ideas, even if they don’t naturally go together. There’s a very human desire to do these things and apply logic and reason to a species that can be inherently chaotic, messy, and illogical. There are definitely pangs of Rear Window in Gazer. In fact, the film feels like a very post-modern deconstruction of many of Alfred Hitchcock’s films, albeit with a more horror-centric slant. However, there are also traces of other polarizing character studies like Lee Chang-dong’s Burning, Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, or Chan Wook-park’s Decision to Leave. Gazer is about making sense of madness before said madness consumes the individual and they’re too far gone to parse out what’s real. It’s a curious study in point-of-view storytelling and how to weaponize an unreliable narrator for maximum effect.

Unfortunately, the film struggles to see the forest for the trees and gets lost in the fog.

Gazer revolves around Frankie (Ariella Mastroianni, who also co-wrote the film), a conflicted individual who suffers from dyschronometria, which affects her ability to know how much time has passed. All that Frankie wants to do is provide for her daughter, Cynthia, but this meager task becomes increasingly challenging. Frankie’s crushing cognitive deterioration puts her in a situation where she’s told to more or less give up and that hope is a fool’s errand. This leaves her in a fragile, frightening place, which pushes her to immerse herself in a dangerous situation, with the hope that she’ll be able to cash out and give her daughter the stability and security that she deserves.

”What do you see?” is treated like a grounding mantra for Frankie, but it’s also a distillation of her growing obsession. She relies on audio tapes to determine how much time has passed and what’s going on in her life, which adds a Memento-like quality to her plight. This also helps feed into the film’s neo-noir mystery angle, which occasionally feels forced, despite how it’s Gazer’s driving force. Gazer wants its audience to get lost in this confusion and disorder, which becomes a double-edged sword, and one that’s frequently too sharp for the film to handle.

Frankie’s situation intensifies and Gazer is a film that’s rich in palpable desperation that hangs over Frankie and has her eager to escape from her life. Her loss of time and a compulsion to daydream is a symptom of her dyschronometria, but it’s also how she survives and cuts through life’s static. Unfortunately for Frankie, the static is sometimes too deafening to overpower. This desperation and hopelessness defines Frankie, but it’s also what sets her on this troubling trajectory that has the potential to change her life – or at least make it marginally less suffocating.

Gazer is such a bleak experience and it turns into a constant meditation on loss. This helps the audience feel as vulnerable and frightened as Frankie, but it begins to be too much to bear at times. Despite the free-floating dread and sadness, the film still makes sure that the audience roots for Frankie and wants to see her get any type of win. It’s at least successful on this front.

One of the reasons that Gazer is such an uncomfortable experience is because there’s rarely an escape from Frankie’s intense thoughts. The film is guilty of an obtrusive expository voiceover that’s used a little too often and it would benefit from trusting its audience a little more. It’s really hamfisted and overdone. It’s admittedly a noir trope, but it could still be better implemented and more effective. Gazer at least concocts a plausible reason and device for Frankie to always be waxing poetic. This detached voiceover, when it works, conjures an energy that’s reminiscent of Fight Club with how it puts up a tough front and tries to keep the audience at a distance as a way for her to have any sort of agency and control in life. However, the final act features Frankie literally explaining everything that’s happened in the movie. This reduces the impact and robs the movie of sticking the landing, despite how it temporarily flirts with some intriguing ideas and developments.

Gazer grows more confident and accomplished as it goes on. There are even long stretches of the film where it almost entirely ditches the voiceover in favor of more intuitive, cryptic filmmaking that’s much more natural. It eventually reaches a really interesting place in its final act, but it takes just a little too long to get there. There are also occasional glimpses of Cronenbergian body horror, in particular Videodrome. These are often Gazer’s strongest moments, but they’re very few and far between.

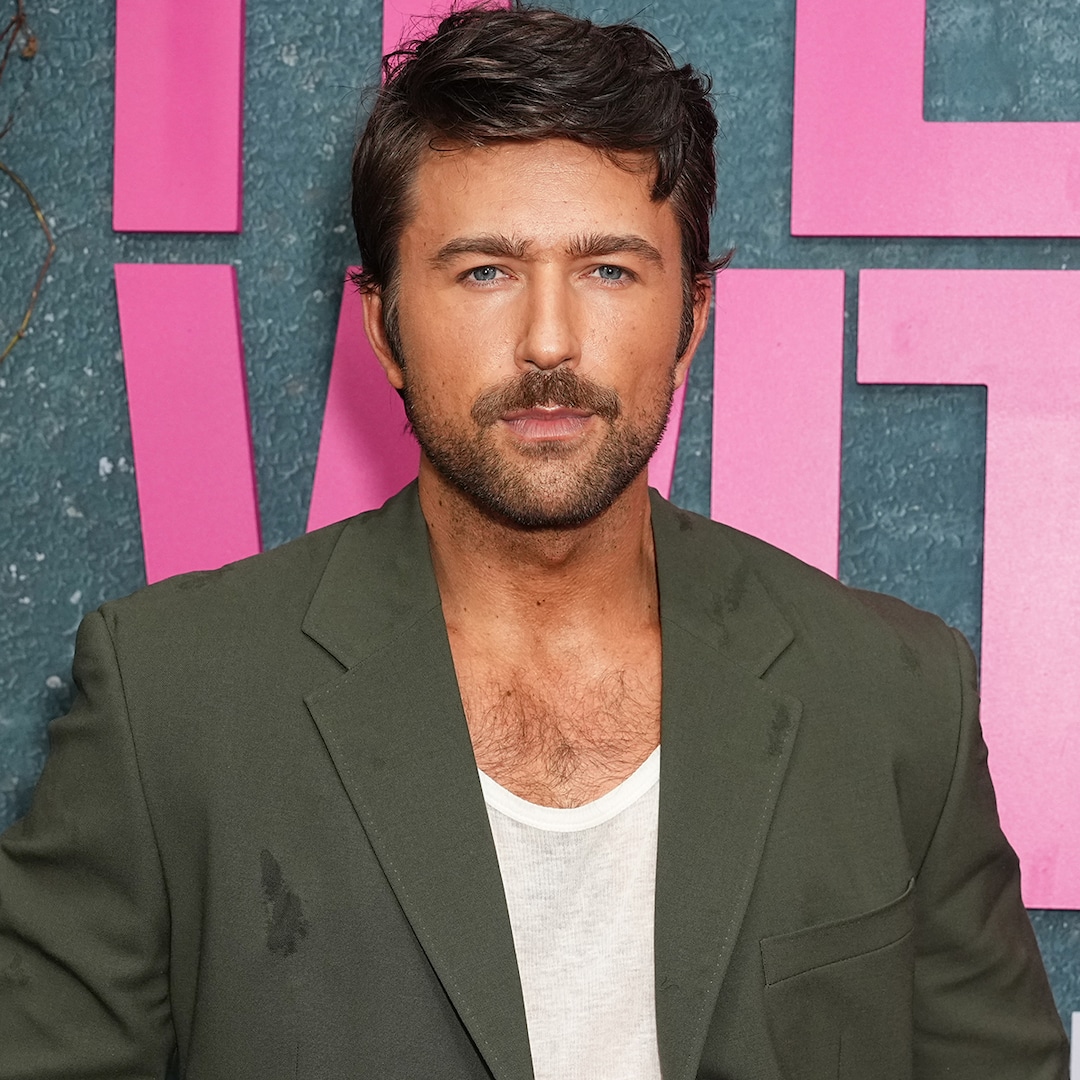

Gazer has its heart in the right place and effectively taps into the paranoid energy of a bygone era. It’s a dark film that isn’t afraid to psychologically torture and overwhelm its characters. However, there are too many imprecise moments that immerse Frankie – and the audience – in darkness and then struggle to find their way out. Gazer fails to become a pivotal horror text on voyeurism, but it’s a promising step forward for indie filmmaker Ryan J. Sloan.

Gazer premiered at the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival 2024.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/12/24/622/n/1922564/9eb50f2c676abd9f1647c5.05876809_.jpg)

![Cody Johnson – I’m Gonna Love You (with Carrie Underwood) [Official Music Video] Cody Johnson – I’m Gonna Love You (with Carrie Underwood) [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/yy9PuYMU29g/maxresdefault.jpg)